Covert agent Cyril DePaul thinks he’s good at keeping secrets, especially from Aristide Makricosta. They suit each other: Aristide turns a blind eye to Cyril’s clandestine affairs, and Cyril keeps his lover’s moonlighting job as a smuggler under wraps.

Cyril participates on a mission that leads to disastrous results, leaving smoke from various political fires smoldering throughout the city. Shielding Aristide from the expected fallout isn’t easy, though, for he refuses to let anything—not the crooked city police or the mounting rage from radical conservatives—dictate his life.

Enter streetwise Cordelia Lehane, a top dancer at the Bumble Bee Cabaret and Aristide’s runner, who could be the key to Cyril’s plans—if she can be trusted. As the twinkling lights of nightclub marquees yield to the rising flames of a fascist revolution, these three will struggle to survive using whatever means—and people—necessary. Including each other.

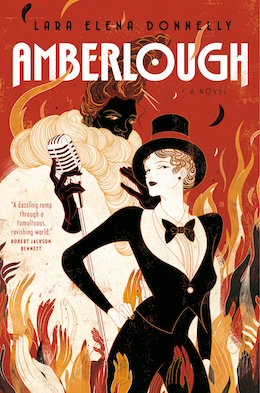

Debut author Lara Elena Donnelly’s spy thriller Amberlough is available February 7th from Tor Books. Come back every Wednesday from now until the release date for additional chapters!

Chapter One

At the beginning of the workweek, most of Amberlough’s salary-folk crawled reluctantly from their bed—or someone else’s—and let the trolleys tow them, hung over and half asleep, to the office. Amberlough City, eponymous capital of the larger state, was not home to many early risers.

In a second-story flat on the fashionable part of Baldwin Street—close enough to the river that the scent of money still perfumed the air, and close enough to the wharves for good street food and radical conversation—Cyril DePaul pulled himself from beneath a heavy duvet of moiré silk. The smell of coffee was strong outside his nest of blankets. An early spring storm freckled the bedroom windows with rain.

Though this was not his flat, Cyril slipped from bed and went directly to the washroom without hesitation. He ran a wet comb through his hair, brushed his teeth with cloying, violet-flavored toothpaste, and borrowed the dressing gown hanging on the bathrail. Despite Aristide’s penchant for over-warming his rooms, the last of winter lingered in the tiled floor. Cyril left the cold mosaic of the washroom behind and gratefully took to the plush carpet running the length of the hallway. Its tasseled end debouched onto the parlor, where he met the maid balancing an empty tray.

“He’s at the little table, Mr. DePaul,” she said, without so much as a blush.

“Thank you, Ilse.” She had charming dimples when she smiled.

At the far end of the parlor, where it joined with the dining room, the corridor belled outward into a breakfast nook bracketed by windows. An elegant, ochre-skinned man sat at his ease in one of the gilded chairs. Reading spectacles rested halfway down his dramatic nose—narrow at the top, wide at the base, deeply curved: as if a sculptor had put her thumb between his eyes and pulled firmly down. His thin lips were arranged in a pout practiced so often in the mirror it had become habitual.

He held the society pages of the Amberlough Clarion against one knee. The rest of the paper—all the crosswords done, and still damp from the storm—was scattered among a silver coffee service set out for two, and dainty plates of almond pastry. As Cyril sat down at the unattended coffee cup, Aristide snapped his paper and said, without looking up, “Finally. I was beginning to wonder if you’d d-d-died in your sleep.”

“And miss the pleasure of your company at breakfast? Never.” Cyril poured for himself, luxuriating in Aristide’s affected stutter, and the soundless slip of coffee against the shining glaze of his cup. “Are you finished with the front page?”

“Ages ago.”

Cyril reached for the paper and grimaced when the wet ink left streaks on his palm. “Been up long?” He asked the question casually, but over splotchy headlines he catalogued Aristide’s appearance with strict attention: satin pyjamas under a quilted dressing gown, the same set he’d—almost—worn to bed. His tumble of dark curls had been swept casually over one shoulder, but they still showed traces of damp. A flush lingered across his cheeks. He’d left the flat already this morning, but changed back out of his clothes. Something illicit, then, and Cyril was not supposed to notice. Obediently, he ignored it, just as Aristide ignored his scrutiny, and his question.

“Eat.” Aristide pushed one of the pastries across the table. “Or you’ll be late to work. I shiver to imagine C-C-Culpepper in a fury. She’s frightful enough as it is.”

“Ari—”

“I know, I know. I’m not supposed to know.” He reached two bony fingers into the breast pocket of his dressing gown and removed a slip of paper, folded in half. “And neither should she, right?” Without looking at Cyril, he handed over the cheque. “Discretion, as they say, is p-p-priceless.”

Cyril made the payoff disappear up his sleeve. “You don’t have to remind me.” The money was a symbolic gesture, allowing for plausible deniability. “But I’m glad when you do.” Ignoring the pastry, he drained his coffee cup and stood. “Clothes?”

“Ilse p-p-pressed them. They’re hanging in the wardrobe.”

Cyril dipped down to kiss Aristide on the top of his head. His hair smelled of rain, salt, and smoke. Somewhere on the wharves, then. Probably the southern end, near the Spits. Bad part of town—smugglers docked there, in the wee hours.

Aristide grabbed a fistful of Cyril’s fox fur lapel and pulled, forcing him to bend deeper, until they were face-to-face. “Cyril,” he purred, and there was menace behind it. “You haven’t got the t-t-time.”

“Ah,” said Cyril, “but don’t you wish I did?” He kissed Aristide again, on his pursed, displeased mouth. After half a moment’s resistance, Ari gave in and smiled.

The rain was done by the time the Baldwin Street trolley stopped at Talbert Row. Cyril disembarked and joined a bedraggled wave of late commuters all headed for the same transfer.

Wedged at the front end of the trolley car, between the driver’s partition and a dozing woman in a loud plaid suit, Cyril took the Clarion out from under his arm—he’d bought his own copy at the Heynsgate trolley stop—and propped it against his leg. The headliner was a story about a train station bombing in Totrajov, a disputed settlement on the border of Tatié.

Of the four nation-states in Gedda’s loose federation, Tatié was the most fractious. The only state to maintain a standing army, it had been locked in a bitter territorial conflict with the neighboring republic of Tzieta for generations. Lucky for the rest of the country, federal funds and energy only went to mutually beneficial projects—infrastructure and foreign policy and, particularly relevant to Cyril, national security—so the decades-long skirmishing hadn’t drained the national treasury, just nearly bankrupted an economically precarious Tatié.

By and large, Amberlinians ignored their eastern sibling except as the subject of satire, and an occasional creeping nervousness vis-à-vis Tatien firepower. Though it wasn’t strictly good form, Amberlough’s covert operatives kept a close eye on Tatié. The best of navies was no good against a landlocked, militarized state, and they weren’t the most cordial of neighbors.

Tucked neatly under the gruesome account of the bombing was a smaller headline on the upcoming western election. Parliamentary elections were all offset by two years, and this year it was Nuesklend’s turn. In the accompanying picture, outgoing primary representative Annike Staetler stood next to a young woman with marcelled hair and deep-set eyes. The caption read Staetler endorses Secondary Kit Riedlions, South Gestraacht. Below that, another picture, of a pale, flat-faced man in rimless spectacles, looking down from a podium swagged with bunting. Caleb Acherby stands for the One State Party in Nuesklend.

Poor Staetler. She’d been good to her constituents, and they would have had her for another eight years if she’d let the state assembly dissolve Nuesklend’s term limits. Cyril hadn’t been at the luncheon where Director Culpepper and Amberlough’s primary parliamentary representative, Josiah Hebrides, went to work on her, but Culpepper had come back in a foul humor, filled with apocalyptic premonitions. Staetler was a staunch ally against encroaching Ospie influence in parliament. As long as regionalist Amberlough and Nuesklend stood against unionist Farbourgh and Tatié, things stayed at a deadlock. If Acherby took the primary’s seat… well, he’d always been the brains behind the Ospie cause. He’d had to wait through two election cycles, unable to run for office outside his birth state. Now it was his turn, and he’d have a long to-do list.

He’d probably calm things down in the east, and feed the starving orphans in Farbourgh, but at a crippling cost to Gedda as a whole. Acherby’s aim was unification: the loose federation into one tightly controlled entity. The manifold diversity of Gedda’s people into one homogenous culture.

Sighing, Cyril opened the paper to the center and folded it back on itself, hiding Acherby’s severe expression under layers of cheap newsprint.

He was deep in a conservative opinion piece in favor of further increasing domestic border tariffs—the same tariffs Aristide had been neatly avoiding in the small hours of the morning—when the trolley cables caught and the gripman bawled out “Station Way!”

Cyril disembarked to walk what was left of his commute. The gutters ran fast; bicyclists and motorcars splashed oily water across the footpath as they passed. Behind the marble edifice of the capitol, masts and smokestacks striped the sky above the harbor. Seabirds wheeled and shrieked, peppering the green copper dome of government with their droppings.

Amberlough’s branch of the Federal Office of Central Intelligence Services hid on the top three floors of an unassuming office building, just across Station Way from the capitol’s sloping gardens. Like everything in the FOCIS, the office had its own facetious nickname: the Foxhole.

“Morning, Mr. DePaul,” said Foyles, from behind his racing form. Foyles had presided over the lobby as long as Cyril had been working in the Foxhole, and prob ably twice again as long as that. Deep wrinkles creased his face, and the tight spirals of his hair stood out in striking white against his slate-dark skin.

Cyril half-waved at him and stepped into the lift, standing back while the attendant shut the grate. He didn’t need to tell her his floor.

The lift paused once, at three, where the clerks and auditors held court amidst the clamor of ringing lacquer telephones, heads bent over pencils and adding machines. Floors four and five were sleight of hand—espionage to ensure the security of the Federated States ofGedda—but three was where the true sorcery happened. The bursar’s team made eye-popping embezzlements into minor calculating errors. Bribes and payoffs dis appeared into endless columns of numbers and names. Agents were paid in secretive exchanges, the intricacies of which could escape even authorizing division heads. The accountants were, to a person, discreet, clean-cut, and scrupulously polite. They terrified the rest of Central.

The attendant scissored the lift grate open and stepped back for a new passenger. A young man in a shabby suit got on, ducking his head of bright copper hair. He smiled at Cyril without making eye contact. Against his chest, he held a sheaf of papers under a fat leather datebook, arms crossed tightly over it all like a shield. Cyril ticked through his mental files, checking names against faces, stories against facts.

Low-level auditor. Been in the office two years. Uncommonly straight, for an Amberlinian: He’d never tried his hand at extortion. Painfully fair, with a winning tendency to blush when embarrassed. Embarrassed very easily. What was his name, again? Lourdes. Th at was it. Finn Lourdes.

They’d only spoken once or twice—Finn had visited Cyril, just out of hospital, to express Central’s sympathies, and deliver by hand a comfortable bonus and promise of promotion: Culpepper’s blood money.

They ran into each other sometimes in the halls, now that Cyril was settled behind a desk. And anyway, Cyril wouldn’t be working on the fifth floor if he didn’t have a mind for details.

Chapter Two

Across town, near the train yards, a few thin rays of morning sun burned through the clouds and fell through an open window, warming the freckled arms of Cordelia Lehane.

She pushed her hands through Malcolm’s hair. He normally kept it slicked back in a ducktail, but now it stuck up at all angles. Last night’s pomade greased her already-sticky fingers. He turned his face, swarthy against her winter-pale skin, and his stubble rubbed her belly. Sunlight struck threads of gray at his temple. Cordelia traced one strand, her finger sliding through the sweat gathered at his hairline.

“You’re the best thing that’s happened to me in an age,” he said.

She half-smiled and shoved his face away. “Go on,” she said. “I ain’t.”

He pressed his face into the softness of her, between hip bone and navel. The pressure made her bladder ache, but she didn’t tell him to stop. The pain mingled with the tingling comedown of sex.

“I’ll prove it,” he said, and pushed her thighs apart.

“Mal.”

He didn’t lift his head. She grabbed his hair and pulled his face up. “I’m dying for the toilet,” she said. “Give me half a minute.”

He laughed and let her go, rolling over onto his back to fill the space she’d left. “You’re a treasure,” he said.

“Even treasures gotta piss sometimes.”

When she went to flush, the pipes groaned and shuddered.“Queen’s sake. Ring round a plumber once in a while, why don’t you?” She rinsed her hands in water that came out reddish brown with rust.

“Can’t afford to. The washrooms at the theatre’ve got to be done over this month.”

“Maybe you ought to move in there.” She came back to bed and flung herself across the sheets. A breeze, fresh with high tide brine, rolled through the room. Cordelia shivered and moved into the warm curve of Malcolm’s body.

“You don’t take care of yourself,” she said, but she didn’t put much into it. Half a shake of the head, a rueful smile. “You’d sell your own ma if it’d bring in a bigger crowd.”

Malcolm cuffed her gently on the side of the head. “My old man, maybe. But never Ma. She was—”

“The jewel of the peninsula, I know.” She rested her face on the hard curve of his bicep, staring up at his seamed, stubbled face. “The finest dancer in Hyrosia.”

“She would’ve loved to see you,” he said, drawing a calloused hand through her hair. It caught, but she didn’t complain. Malcolm’s eyes changed when he talked about his mother: The flint went out of them. “My mother would’ve loved you,” was as close as he ever got to “I love you.”

But everybody knew—especially Cordelia—that Malcolm only loved the Bee.

His mother had given up her stage career to come north and marry. And it had gotten her nothing but accounting books and two sons dead at sea, killed by Lisoan pirates somewhere south of her home country. Her youngest, Malcolm, she’d kept at home despite her husband’s squalling. Malcolm heard all her stories, saw all her tintypes and mementos. Promised her she’d have a stage to walk again.

When she died of fever, he took what she’d left him and abandoned his father’s shipping company for the boards. All his love for Inita Sailer went into making a go of the Bumble Bee Cabaret and Night Club.

“How’s the new routine?” he asked. “Speaking of dancing.”

She shook her head. “I got it all down, but the orchestra’s having trouble.”

Malcolm sat up and threw his legs over the edge of the bed. “I’ll ask Liesl about it.” He picked his watch up from the bedside and flipped it open. “Better be getting over there. Got a delivery coming in for the bar.”

“Ytzak can take care of it,” said Cordelia, wrapping her arms around Malcolm and tangling her fingers in the dark hair across his chest. She tried to pull him back into bed, but he resisted.

“No, he has the morning off—said his ma’s sick, but you know he’s courting that razor who plays bass in Canty’s band, and he was a little too eager to run out last night.”

“So drag him in,” said Cordelia, hooking one leg over Malcolm’s thigh.

He laughed and pinched her, but stood nonetheless. She let him go and collapsed against the bedspread, giving him her best pout.

“You learned that one from Makricosta,” he said. “You know it won’t work on me.” Pulling a threadbare cotton undershirt over his head, he added, “You’re welcome to hang around here, if you like. But I won’t be back before curtain, almost sure.”

Cordelia sighed. “You gonna ask me to run to the cleaners for your swags again?”

“Be a swan?” He swooped in and kissed her cheek. “Tell Kieranto put it on the account.”

“You owe him half a fortune this month already.”

“He knows I’m good for it. Especially once this new show’s up and running.” Malcolm slipped his braces over one shoulder then the other, and hooked his jacket and hat down from the back of the bedroom door. “Later, spicecake.”

“Remember to talk to Liesl!” she shouted after him. The downstairs door slammed, rattling the bottles of hair tonic and cheap cologne on Malcolm’s nightstand.

Cordelia fluffed a ratty pillow and leaned back, staring at the cracked plaster ceiling. The Bee did a swift trade. Malcolm only lived in such a shambles because whatever he made running the theatre went right back into it.

Not that she was complaining. Every stage-strutter in Amberlough wanted a spot on the Bee’s pine boards. Malcolm paid his performers better than any place in the city—still a pittance compared to salary folk, but Cordelia padded her pockets out with dealing a little bit of tar on the side. It wasn’t pretty work, but it was steady and it turned a profit.

Speaking of, she was due to make a pickup from her man on the docks this afternoon. Malcolm didn’t clock she had a sideline, and wouldn’t approve. But he wouldn’t have to know, as long as she got him his swags on time, in fine condition.

Malcolm’s evening clothes hung from the luggage rail, swaying with the motion of the trolley. Rain struck the windows. Everything smelled woolly and damp. Cordelia was running late, but the commute was so cozy, she didn’t mind. It had been a good afternoon—the pickup went smooth, and after, she’d swung by Tory’s.

He was tucked against her side now, warm and noisy, chatting on about… oh, who knew what. He talked all the rotten time. Half of it she didn’t clock, but the sound was pretty. He tried to keep his Currin burr tamped down, but it always came out when he got pinned about something or—and she’d been pleased to find this out—when he was in bed.

Tory tugged her coat sleeve. “Our stop.” Passengers were standing in the aisle, taking down packages and purses, tying their scarves tighter and flipping their collars up against the rain. “Come on,” he said, jumping down from his seat. His head was on a level with the other passengers’ bellies, but the way they made space for him, you’d never know.

They both stepped in the gutter, and Cordelia shrieked at the cold water soaking through her shoes. Tory waved her over the curb, toward a pair of wet metal chairs under the awning of a cafe. On the corner, a Hearther evangelist had set up a soapbox for his street sermon. He’d been a regular feature of Temple Street for going on two years now, trying to convert fallen stagefolk and the punters who came to cheer for them. Lately he’d taken to wearing a gray-and-white Ospie sash. Most of the Hearther congregations in town were backing the Ospies. Cordelia was fine with that. Keep the prissy people together and let them entertain themselves, however they proposed to. Folk in the theatre district had better things to do.

Across the street from the preacher, the Bee stood tall between a wine bar and a casino, brighter than any other theatre on Baldwin Street. Brilliant swirls of white bulbs, lit against the gray afternoon,made the golden moulding of the marquee shine twice as bright. Richly illustrated posters glowed in their illuminated frames across the front of the building—Cordelia spied herself just to the left of the entrance, all red ringlets and black roses, her lips stung puff y by the swarm of gilt bees that spiraled around the poster border.

“Check me,” said Cordelia, hauling down the collar of her dress. “No marks?”

Tory looked over each shoulder, conspiratorial, and then buried his face in her chest. “No marks.” His voice was muffled.

The preacher saw them, lifted an accusing finger, and started hammering hard on modesty and decency and good, upstanding citizens.

Cordelia made a rude gesture at him, then grabbed Tory’s ears and hauled him out of her tits. “Stop it! Be serious.”

“No marks,” he said again, brushing his thumb down her breastbone. “I know Malcolm does his damnedest to keep from splotching this bonny fair skin—”

“Sometimes even his damnedest ain’t damned enough.”

“—and I wouldn’t want to spoil it either. Besides, he might recognize the teeth marks.” Tory grinned like a nutcracker. “And jealous old Sailer wouldn’t stand for that.”

Cordelia smoothed the damp garment bag over Malcolm’s tailcoat. “Let’s go in. Before we’re any later.”

Tory stood on his tiptoes to kiss her, quickly, and then set off across the street with the preacher howling behind him. He caught her eye from beneath the marquee. Standing just under the illustrated Cordelia in her ring of black roses, he reached up and mimed pinching her nipples, where they would be beneath the garland of flowers. She made the same rude gesture at him she’d thrown at the Hearther. He laughed, then hauled open the heavy black-and-gold doors and disappeared, stumbling over the threshold.

They weren’t supposed to go in through the front, but Malcolm held Tory pretty dear and let all sorts of his mischief slide. Cordelia didn’t feature him giving a pass for ducking under her skirt, but what he didn’t clock wouldn’t bruise him.

She waited a moment longer, picking absently at the soggy edge of the garment bag. The rain slacked off, but a sudden wind off the harbor shook droplets from the budding plum trees, spattering the restaurant awning. Gathering up her purse and Malcolm’s swags,she waited for the street to clear, then dashed across between the puddles and slipped down the alley that ran along one side of the Bee.

The stage door was propped open with a chair to let a breeze into the stuffy backstage corridors. Stella, one half of the twin acrobat and contortion act, sat in the chair smoking a hand-rolled cigarette. Cordelia caught a sweet whiff of hash. Stella got bad butterflies—her sister Garlande was the showy one.

“Sorry,” mumbled the acrobat, and stood aside to let Cordelia through. The corridor was mostly bare beams, a bit of plaster here and there, stairs leading up to the costume loft. A stagehand sat on the edge of the staircase, retaping Garlande’s trapeze and flirting with a seamstress making last-minute repairs. Someone was listening to a record; the shoddy walls muffled and distorted the strains of a smooth-voiced crooner. Sawdust and greasepaint musk hung in the air.

She had to pass Malcolm’s office to get to her dressing room, and as she neared the open door, she braced herself for a hiding. But he was already shouting at somebody, and it wasn’t her. The new tit singer, Thea Marlow, stood in front of Malcolm’s great scarred slab of a desk, hunched up like a naughty schoolchild waiting for the switch. So, Malcolm must have talked to Liesl, and the conductor had put the blame for the shoddy number on Thea. All things fair, she did have awful trouble with the key changes. Tit singer was a hard sort of job if you had half an interest in naked girls, and judging from Thea’s saucer-eyes whenever Cordelia went up onstage, she wasn’t cut out for the task.

Cordelia hooked Malcolm’s swags onto the doorknob and tried to slip away, but he caught her. Instead of scolding her, he just said, “Delia, Antinou’s tonight? Tory’s treat—he owes me.”

She didn’t want to think of all the dirty jokes the dwarf comedian would make of that. Instead she nodded, and blew Mal a kiss.

As Cyril was getting ready to leave for the day, his telephone brayed, startling him from his latest report out of the train yards.

It was one of the switchboard kids, a girl with a little bit of a lisp. “Mr. DePaul? The skull wants to see you.”

“Thanks, Switcher.” By tradition, all the kids crammed in the exchange room were called Switcher. Cyril tipped the pages of the report into his briefcase and locked it up, then put his coat overhis arm and went down the hall.

Culpepper’s personal secretary, Vasily Memmediv, was in his late forties or early fifties, but his thick, dark hair was only barely touched with gray. The lines that marked his hawkish face cut hard and full of character at the edge of his nose and beneath his deeply set eyes. Cyril had briefly nursed a terrible passion for Memmediv, but rumors put him firmly loyal to Culpepper, in more ways than one.

Cyril rested an elbow on the edge of Memmediv’s desk. “Switcher said the Skull wants to see me.”

“Director Culpepper,” he said, “asked to see you, yes, before you left.” His Tatien accent had faded with time in the south, but still colored his speech with overemphasized vowels and swallowed, liquid consonants.

As if speaking her name had summoned her, Culpepper’s voice rang out from the half-open door to her office. “Is that DePaul?”

Before Memmediv could answer, Cyril cut in with, “Last timeI checked.” He skirted the scowling secretary and crossed into Culpepper’s lair.

She didn’t look up when he entered. “Don’t be flippant, DePaul. It’s unbecoming.”

“Really?” He flung himself into the chair opposite hers. The vast, cluttered expanse of her desk stretched between them. “Usually people are charmed. Maybe you should get your head checked.”

The Foxhole folk called her “the Skull” because she kept her hair shaved close. Bones and muscles showed sharply under the dark skin of her scalp. When she ground her teeth, as she was doing now, the grim movement of her jaw rippled beneath the faint shadow of razored curls. That was what they called her type, in the city: razors. Women in well-cut suits with their hair shorn close, posing and snarling at one another like big cats, their sparks tucked snug under their arms. He didn’t envy Vasily—razors tended to be as sharp in temperament as their namesake was in function.

“You’ll need your head checked if you don’t shut up and pay attention,” said Culpepper. “I’ll put the dents in it personally.”

Case in point. “Oh, Ada. I love it when you’re cruel.”

She crossed her arms. “Less carrot, more stick? Is that the secret I’ve been missing all these years?”

“I’m ruined for a soft hand, since early days. My first was whipper-in with the Carmody hunt.”

“Spare me,” she said, falling against the high back of her chair. The leather upholstery creaked. “You’re saying if I slapped you around a little, your rag taggers would finally get it together to burn Makricosta’s network?”

“Don’t be ridiculous. With the border tariffs so high, people like him are the only thing keeping us out of a civil war.” Besides, Aristide’s smuggling crews had taken on a little extra work ferrying refugees into the city. Ospie supporters—blackboots—roamed the streets in Farbourgh and Tatié, making life hard for immigrants, writers, radicals, wind worshippers, cultists of the Wandering Queen… The blackboots had their own little streets in Amberlough, too, but the ACPD didn’t like them, and they knew it.

“I want to think,” said Culpepper, fingers at her temples, “that the stability of Gedda hinges on more than illegal commerce.”

“Ada, if the northeast couldn’t sell through smugglers, they’d—”

“Throw their lot in with the Ospies? Perhaps you haven’t noticed, DePaul, with your face between Makricosta’s thighs, but we’re past that point. Pinegrove and Moritz were both elected by overwhelming majorities, and the Ospies have been taking secondary seats left and right.”

He let the sexual snipe slide by unaddressed. “I was going to say they might secede. Or worse, collude to overthrow the parliament.”

“Secede? They need our docks. Until Moritz reaches some kind of agreement with the Tzietans, the harbor at Dastya is a war zone. Forget exporting overland. You saw today’s headlines: Westbound trains are targets for Tzietan terrorism. And Farbourgh is just a tragic novel in three volumes. Mountains, rocks, and blighted sheep. What would they do without federal aid? No, secession isn’t in the cards.”

“So that leaves a coup.” He wanted her to laugh. She didn’t.

“You’re right, you know.” She sighed. “I’d love to tear you up and down over Makricosta—don’t give me that look. How much does he pay you to keep his business out of your reports? Or is it just the sex? Or—mother and sons, don’t tell me you’re in love.”

Cyril snorted. “Ada.”

“He’s bent stronger rods, don’t doubt it.”

“You should really think about things like that before you say them.”

“You weren’t even supposed to have contact with him—Cyril, I’m serious, stop laughing. Division heads run agents, they don’t pretend to be them.”

“I was! I—I am. Ada, nobody knew how deep he had his hooks into the market, and we wouldn’t have found out if… His name kept coming up in dispatches, all right? And none of my foxes could get close to him. Or he made it worth their while not to.”

“But you’ve gotten very close indeed. Good job.”

“What happened to tearing me up and down?”

“Oh, I’m pinned about it; don’t think I’m not. But it proves you still know your way around fieldwork.”

Cyril’s hand jumped. He covered by reaching for his cigarette case. Culpepper pretended not to notice, but she couldn’t fool him. They knew each other too well. Before she was the Skull, implacable Queen of the Foxhole, Culpepper had been Cyril’s case officer. Good work saw her promoted to assistant director, and then director, of the Amberlough chapter of the FOCIS while he was still out running under a work name.

“Look, Cyril.” Culpepper sighed and put her hand over her eyes. “With the job you’ve been doing lately—or haven’t been doing, more like—we both know you’re not cut out to play division head; you don’t have the right temperament. I want to send you back into the field.”

He was going to be sick. He could feel the bile creeping up the back of his throat.

“You’re what, thirty-five?” Culpepper, who was herself perhaps twenty years older, looked him up and down. “You’re too young to be behind a desk. You should be out earning your position, not rotting in it. You know Yeffa, over in personnel? We ran her until she was in her sixties.”

Cyril put a straight to his lips but didn’t light it, not trusting his traitorous hands. His current title—Master of the Hounds, Central slang for the division head who played police puppeteer—was guilt-reeking restitution, a courtesy Culpepper had paid him when his last action went sour.

“Besides,” she said, still talking, in that too-casual way that flagged all her serious conversations, “you’re probably bored to tears.”

Bored. Once, it would have been true. Boredom was Cyril’s chief failing. He’d been bored as a child, and it had made him mischievous. He’d been bored at university, and it had nearly gotten him expelled; only the timely intervention of one of Culpepper’s talent spotters had saved him from being sent down in ignominy. And he had been bored behind the desk, a disinterested operator directing the moves and countermoves of domestic espionage. Smugglers and tax dodges, money laundering and corruption. Old hat to any Amberlinian. Bored, but afraid, wretched with cowardly self-loathing and the pain of convalescence. Bored, until Ari had made things interesting.

“Cyril.”

His attention whipped back to Culpepper, who hadn’t stopped talking. “Sorry. What?”

“Bascombe’s gone.”

“Ira? How?”

She locked eyes with him. “Tatié was your purview once. How do you think?

“Dead?”

She shook her head: half rue, half negation. “Just… gone. Tatié’s Foxhole is getting smart. They know we aren’t keen on the whole Dastya for Tatié gambit; think how much tax revenue Amberlough would lose if Tatié didn’t rely on shipping down the Heyn.”

“Shake with the right, shoot with the left?”

“And use a good suppressor, exactly. They learned from… last time. No trace. No messy politicking. But they know we know. And that we’ll feel the squeeze.”

Mother’s tits, he would defect to Liso if she tried to send him back. Taking over for Bascombe, he’d be running a network, rather than doing the work direct. But barely safer, for that. It was unofficial cover, spying on the other states within Gedda; if they caught you, you were on your own.

His throat already felt thick with the dust of no-man’s-land:those blasted, burnt steppes between the orchards and the sea. Hewas back amongst the tattered khaki ranks of Tatié’s armed forces, in the stuffy chambers of cigarillo-smoking officers. Dry earth and endless sky, the smell of blood and cordite…

“But you’re not headed east,” said Culpepper, snapping the thread of his memories. From the ill-concealed pity on her face, she knew what he’d been thinking. “We’re promoting one of our Hellican operatives—”

“Poor fox.”

“Be honest, Cyril. You would take Tatié over the Hellican Islands. Even now.”

He wouldn’t. He had learned: Better bored than dead.

“Anyway. He’d been building an action for us, but the whole thing’s easily moved to a new agent.”

“So you’re handing it to me.”

A shallow nod. “The work name is Sebastian Landseer. A wool merchant. Bit of a playboy—never at home. Skiing in Ibet, snow-birding in the Porachin Gulf. Polo, yachting. You know.”

“I begin to see your logic.”

“In choosing you? Yes. It’s hard to teach someone that kind of privilege. I know what your parents settled on you in their will; very generous, given Lillian was the heir outright. You won’t have to pretend on this action. Not much, anyway.”

“All right, all right.” She was going to make him ask. “Tell me, then. What’s going on?”

“The election.”

Cyril reached for the table lighter, finally remembering his cigarette. “Acherby won’t win.”

“He will if he throws it.”

“He won’t. Ada, he’s got a pry bar for a spine. He doesn’t bend for anything. Just bulls at it straight and hard until it breaks.”

“He’ll bend for this. Three primary reps, and a majority in the lower assembly? Do you know what he could do with that?”

“I have some idea.”

“Be serious, DePaul. The Ospies want Amberlough knocked down—they think we’re impeding trade, sacrificing Gedda for the sake of state interest. Pinegrove and Moritz have already endorsed Acherby, and intelligence out of both capitals says they won’t stop there. They want to impeach Josiah.”

Cyril froze with the lighter wick halfway to his mouth. The flame wavered in his caught breath. “Ada. There hasn’t been a primary impeached in forty years.”

“You don’t need to give me a history lesson. I’m out of the schoolroom.”

“Sorry.” He lit his cigarette and exhaled a thin, artful column of white. Josiah Hebrides had been Amberlough’s primary representative for six years, two-thirds of his allotted term, and the mayor of Amberlough City for eight years before that. He was crooked as a kinked zipper, but charming, and his equally unscrupulous constituents adored him. If he wanted an unprecedented second term as primary, he had only to reach out his hand and take it; none of Staetler’s nobility for him. “Stones, Ada. This is what you throw at me, first thing back?”

“You’re a sharp fox, or you were. I’m confident. So don’t let me down.”

“Thank you. That helps me relax.” Tension between his shoulder blades crept up the back of his neck, coiling into a headache.

“I don’t want you to relax.” She tapped a column of ash into her empty coffee cup. “Do you know Konrad Van der Joost?”

“Acherby’s assistant campaign manager.”

“Courtesy title. He runs their intelligence operation.”

Cyril rested his chin on the back of his hand. A small kiss of heat bloomed on his cheek near the tip of his cigarette. “Engage with him?”

“You’ll have to.” She flipped her watch open and blanched.“Sacred arches, is it really? Look, I’ve got to dash.”

“We haven’t finished.” But Cyril’s protest was halfhearted. The longer he put off his full briefing, the longer he could maintain his denial.

“Come back tomorrow morning. Say half eight? I’ll have Hebrides in and all three of us can go over it. In the meantime, the Landseer letters.” She took a thick dossier from her desk drawer and flung it down. It hit the red leather with a smack and slid within Cyril’s reach. “Take a good look, when you get home. Now, if you’ll excuse me, Cross is back from Liso and I want to sit in on her debriefing.”

“Get a few scraps of news from the old country?” It was a joke, in poor taste. Culpepper had never been to her ancestral homeland. Her parents were political dissidents who had fled from Liso long before the Spice War wrenched the north out of the king’s strangling grasp. Her surname had always been Culpepper, never Kuleppah—changed to avoid retribution, even so far from home. Cyril had seen the file.

“I’ll scrap you,” she said. “Get out of here and do your job.”

He should have gone back to his flat and cracked the Landseer dossier, but thinking of it made him faintly ill. Instead, he stopped at a basement wine bar in Harbor Terrace and got pleasantly drunk on overpriced sherry, until the dinner rush pushed him up the narrow stairwell and into the wet dusk.

He really ought to go home and see to his post. Might even be able to trick himself into reading the Landseer letters, if he stuck them at the bottom of the pile. Swinging onto the next trolley headed up the Harbor line, he hung onto the railing until he could transfer north at Armament.

Near the edge of Loendler Park, a shudder of awareness ran along the rows. Heads turned; people murmured. The woman in front of Cyril cranked her window open, and he heard chanting. Whistles. Hundreds of human voices raised, dissonant. The trolley rounded a shallow bend in the road and shuddered to a halt.

The streetcars of Amberlough did not stop in the middle of their routes. Cyril was not alone when he got up from his seat to peer down the aisle.

He couldn’t see much, not around his fellow passengers, and so he sat back down and turned the hand crank to open his own window. The sound of voices was much louder now, and when he removed his trilby and put his head outside, he saw dozens of people standing in the street, bent close to one another, turned black and yellow by the streetlights. Farther up, the crowd thickened, packing Armament Avenue from footpath to footpath, pressed against shopfronts and night-locked market gateways. Residents crowded the balconies above, and hung over their windowsills. Lit cigarettes spangled the dusk.

The trolley driver stood and addressed his passengers. “Can’t go further, I’m afraid. You can either get off and walk, or ride back to Station Way.”

“What’s happening?” asked a woman near the front of the car. She held her straw hat to her chest, glass cherries bright against her white shirtfront.

The driver shrugged. “Prob ably just some of those artists causing mischief in the park again.”

A group of students had staged a rather tasteless piece of performance art in the bandstand last month, but the crowd hadn’t been nearly so big.

“What’ll it be?” the driver asked. “Walk or ride?”

Most of the passengers remained sitting, content to catch the Station Way transfer, but Cyril’s flat was only a few blocks away. He settled his hat back on his head, gathered his overcoat and briefcase, and pushed to the rear doors.

After the close, damp warmth of the streetcar, his first breath of outside air was refreshing. Then he shivered and paused to replace his overcoat and pull on his gloves, slotting his fingers together to push the leather into place. By the time he finished, the trolley was disappearing around the curve of the road.

He slipped into the gossiping crowd and tapped a young razor on the shoulder. She turned, spat a mouthful of tobacco, and cased him with an appraising eye. “Yeah?”

“What’s all this?” He waved vaguely at the people around them.

She shrugged. “Heard there was a march in the park. Some kind of political thing.”

“In aid of what?”

“How am I supposed to know?” she snapped. “Just trying to get to my old auntie’s flat, aren’t I? And now I’m stuck in this mess.”

Cyril tipped his hat and gave her his apologies, then pushed on, doling out “pardon me”s and dodging dirty looks as he maneuvered up the block toward Blossom Street.

“Can’t get through up there!” someone called after him. He ignored them and shouldered on until he found himself at the edge of the park, and face-to-chest with an imposing police officer—one in a long, unbroken line across the pavement.

“Sorry sir,” said the officer, through an impressive array of bristling facial hair. “Can’t let anyone past.”

“Why not?”

“Been an accident.” He had to raise his voice over a sudden swell of chanting from the park.

“Accident? Someone told me there was a demonstration.”

The officer’s neck went stiff. “Suppose you could call it that.”

“Listen,” said Cyril, “I live just up the street. You can see my building from here.” He pointed over the officer’s epaulet.

“I’m afraid I’m under orders, sir.”

Though he was Master of the Hounds, Cyril couldn’t pull rank on an officer; the federal position wasn’t technically a part of the force. Shifting his briefcase from one hand to the next, he reached for his billfold. “And how much are those orders worth? Let’s say, thirty-five?” The officer turned red, but said nothing. “Fifty?”

“Please, sir. I really can’t.”

“Well,” said Cyril, irked to have found the one honest hound in all of Amberlough, “perhaps your friend here can.” He turned to the next officer in line. “This is ridiculous. I live right there. What’s going on that’s so damned important?” He slipped the woman a folded bill.

This officer, younger and slighter than her stubborn colleague, was also more susceptible to bribery. She made the money dis appear.

“OSP demonstration,” she said. “Got a bit nasty. Some hecklers broke in and beat one of the unionists bad. Turned into a brawl, and now we’ve got orders to keep everyone out who’s not a party member.”

“For fifty, will you pretend I’m an Ospie?” Cyril gave the woman a smile that should’ve been charming, but prob ably came off more like a teeth-baring grimace. His face felt stiff with frustration.

The younger officer looked sideways at her neighbor, who was silently projecting a air of deep disapproval.

“I really can’t, sir,” she said, shaking her head. “I’m sorry.”

Cyril let his shoulders slump forward. “Fine. Good luck with this wreck.” He turned away and moved back through the crowd.

Halfway down the block, he body-checked a man in a heavy overcoat who was paying more attention to the police blockade ahead than he was to the two feet in front of him. Cyril staggered back, and the man caught him and set him straight.

“So sorry,” he said. “Careless of me. Are you all right?”

“Fine, fine.” Cyril smoothed the front of his coat. “You’re in an awful hurry for nothing, I’m afraid. They’re not letting anyone through.”

“Not anyone?”

“See that?” Cyril pointed. “I live just there.”

“Awful. And they wouldn’t budge for anything?”

“Not for fifty crisp slices.”

The stranger sighed. “Well, I suppose it’s all to the good. I’d rather an upstanding hound any day of the week.”

Cyril laughed. “You can’t be serious.”

“Deadly so. You’d prefer the agents of justice roll over for a little bit of pin money?”

“If it would get me home with my feet up.” Cyril squinted at the man in front of him. “Where did you say you were headed, exactly?”

“The rally, of course.” He flipped open his coat to show a gray-and-white cockade pinned in his buttonhole. “Election’s coming up. We’ve got to support our people in Nuesklend. Acherby’s fighting for all of us, not just the western constituency. For honest, upright folk who are sick of the way things are. Sick of the graft and embezzlement and the coastal blockade. People ought to know we’ve got a vocal presence, even in Amberlough.”

“Vocal, certainly. Caterwauling, even.” Cyril snapped up the collar of his coat and turned away. “Excuse me.”

“That’s right, walk away.” The man’s shout followed him down the street. “Afraid of a little civil discourse? Afraid we might be right?”

He knew he shouldn’t, but he turned and shouted back. “If you want to scare me, do a little better in the polls.”

The man turned red, and blustered, and Cyril left him there before he could come up with a response. Bitterly, he reflected that the polls didn’t matter anyway, if what Culpepper had told him was true. It gave him a modicum of pleasure to realize he had misled the man; the hounds had said they would let Ospies through, but this fellow would prob ably turn around and go home.

Unfortunately, Cyril didn’t have that option. Without the prospect of a change of clothes and a tumbler of rye with his landlord’s excellent supper, exhaustion and disgust threatened to break over him like a gray wave. Nothing for it but to keep moving. His post would have to wait. He made his slow way back to the edge of the crowd and followed the streetcar tracks to Buttermarket.

The sky lowered, threatening more rain. He sat on a bench under the meager shelter of a budding pear tree, briefcase on his knees, waiting for the southbound trolley that would take him to the Harbor line, to Temple Street, and the Bumble Bee Cabaret.

Excerpted from Amberlough © Lara Elena Donnelly, 2017